System folders are folders not intended to be accessed by the user. They help applications and the operating system run, providing support and resources. They’re the layer that allows users to manipulate the host through applications and programs. Some are hidden, and some are not, but almost all are accessible to the user in some way.

But what are the different system folders for? What’s “bin,” and how does it help your computer? We will examine the most commonly-referenced system folders below.

The /System folder itself on your Mac doesn’t contain much. We will first look at its contents before moving on to other, deeper system folders.

Do not add to, remove, or modify system folders and files. You can browse safely, but adding, removing, or modifying files or changing the folders themselves can have unpredictable – and sometimes system-breaking – consequences. If you must experiment, make a bootable clone of your Mac before proceeding.

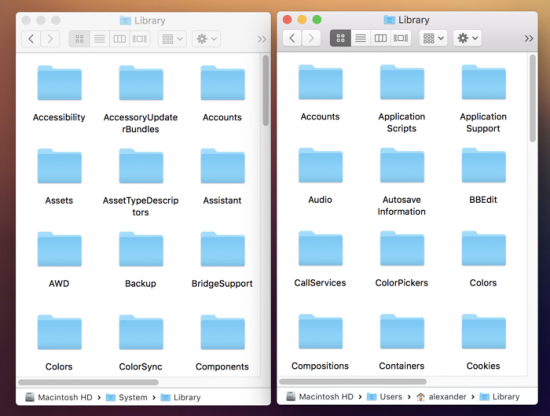

Library Folders: /Library, /System/Library and ~/Library

Library folders are closest to the user. They are created by applications for their use. Applications add, remove, and modify files over the course of their operation. Applications are basically free to do what they like when it comes to placing files in the Library, but most follow an established tradition of putting support files in the Application Support folder.

You’ll find a huge variety of files and folders in both the single-user Library folder (found at ~/Library), the library accessible by all users (/Library) and the system library folder (/System/Library). These files save preferences, application databases, metadata, plugins, saved application states, system profiles, cookies, and much, much more.

You can dive in and start looking around, but make sure to do so on duplicates of the files, as not to break your existing programs. While Application Support settings generally can’t crash the app or make it non-functional, they can erase user preferences if formatted incorrectly, which is annoying.

Why are there so many Library folders in macOS?

Three libraries might seem like a lot, but there is a logic to it. Files in /System/Library support macOS system applications. Files in /Library support applications accessible by all users. Files in ~/Library support applications installed by that user. You will sometimes see duplication between /Library and ~/Library, which allows an app to be accessible to all users while also saving preferences for an individual user.

/System/Library doesn’t hold a lot of functionality for the average user, as it focuses on system applications infrequently seen or accessed by the user. You won’t find an Application Support folder there because it’s not accessible by user-installed apps, and macOS uses a slightly different support structure for core applications. However, you will find /System/Library/Extensions, /System/Library/LaunchAgents, and /System/Library/LaunchDaemons. These are explained in more detail below.

The area of most interest to users is generally ~/Library, followed by /Library.

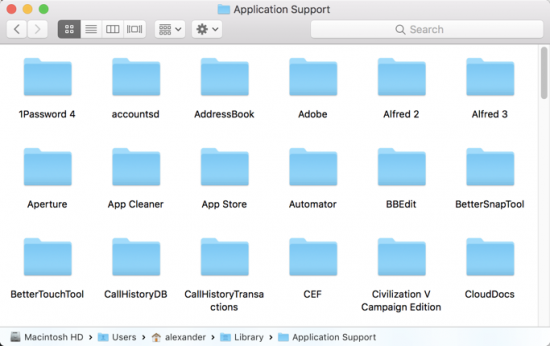

/Library/Application Support and ~/Library/Application Support

The ~/Library/Application Support folder is the most frequently accessed Library folder. Here, applications save files needed for their operations. Away from the user’s data folders, these files can be segregated to avoid contamination or modification.

When users access this folder, it’s to change the way a program works in a way that is unsupported by the default settings or to fix some kind of cache or database error. Removing a program’s Application Support folder is a good way to reset the program to its default state and force a clean start. And if you want to hack around in an application, you’ll find yourself in that program’s Application Support folder before too long.

The same goes for /Library/Application Support, though those settings are for system-wide functionality. You’re almost always better off editing the Application Support files in your user directory.

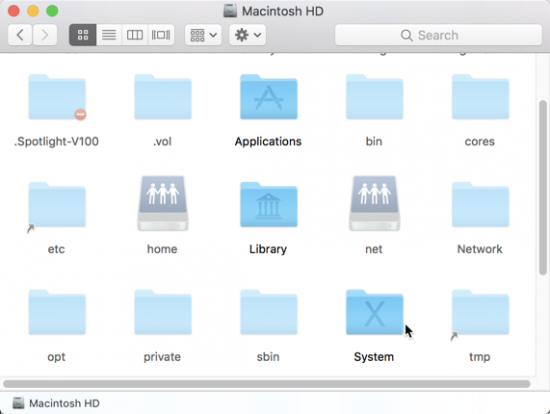

Unix Folders: /bin, /sbin, /usr, /var, /private, /etc

macOS is built on top of a Unix kernel. This means that much of its deep functionality is based on Unix. So apart from the higher-level macOS system folders, you’ll find Unix folders as well. These folders allow macOS to use Unix systems to support the more complicated macOS infrastructure that most users interact with. If you come from Linux, you’ll recognize many of them, as they are basically the same.

These folders are universally hidden, so you’ll need to reveal hidden files to follow the tour. To reveal hidden folders in Finder, press Command + Shift + . which will toggle hidden file visibility.

You’ll find quite a few Unix folders in your home directory. The most notable are /bin and /sbin, /usr, /var, /etc, and /private.

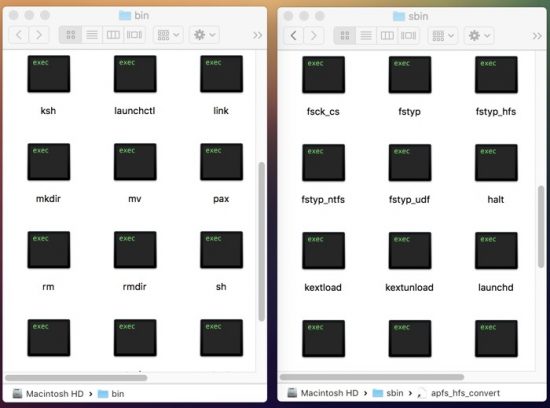

/bin and /sbin both hold binaries, which is another name for programs run in Terminal. sbin holds binaries needed for booting, restoring, recovering, and repairing the system without a file system mounted. /bin holds essentially user commands for use by all users.

On macOS most of the filesystem-mounting binaries in /sbin are hard linked to macOS file system plugins in the /System/Library/Filesystems folder. Hard links allow a folder to appear to be in two places at once on the file system. This means that the /sbin binaries are accessible from either /sbin (for more basic Unix programs) and /System/Library/Filesystems (for macOS).

/usr contains binaries and libraries used during normal system operation. Files here are used after a file system is mounted.

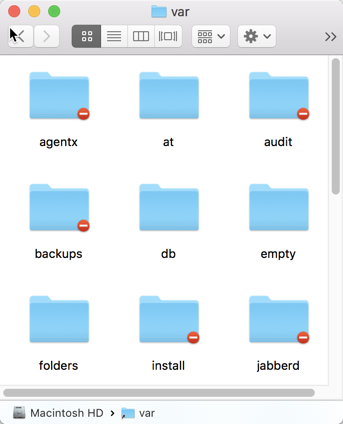

/var contains files the system writes to over the course of its operation, like caches, data libraries, and logs. Var is typically only written to by low-level system applications. On macOS /var is linked to /private/var.

/private contains daemon and command line tool configurations, caches, variables, virtual memory swap files, temporary files, and sleep images. On macOS /var, /etc and /tmp are linked to an identically-named directories in /private. As mentioned earlier, this allows for backwards compatibility with older Unix programs while preserving macOS’ preferred file locations.

If you want to learn about the contents of these folders, you can check out this detailed breakdown of the Mac’s Unix folders.

System/Library/Extensions

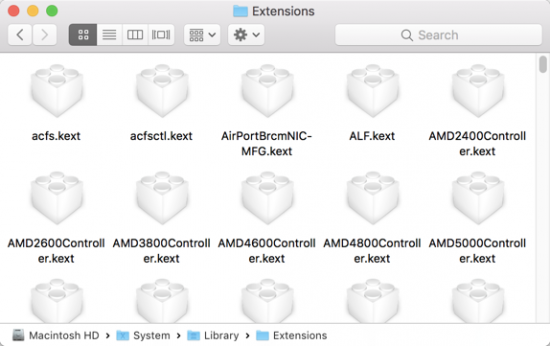

If you’ve ever built a Hackintosh, you’ve heard of System/Library/Extensions. Commonly abbreviated S/L/E, this folder contains “kexts,” or kernel extensions, that expand the functionality of the macOS kernel. Adding kexts helps the macOS kernel communicate with new hardware. If you’re from Windows, kexts are like drivers.

Modifying the contents of this folder is tricky business, requiring careful permissions management. If you want to add or remove kexts on macOS, make sure you do it right.

Agents and Daemons

Daemons and agents run in the background, performing tasks without interaction from the user. The unusual name (pronounced as “demon”) originates with Maxwell’s daemon. In this case, it refers to a small creature performing essentials tasks in the background rather than the common definition of demon as a devil.

Daemons perform system operations and are run by root, while agents are run by the logged-in user. Global agents and daemons can be accessed and run on behalf of any user, while user agents can only be run on behalf of the user that owns their library file.

- ~/Library/LaunchAgents contains user agents run on behalf of the logged in user

- /Library/LaunchAgents contains global agents run on behalf of the logged in user

- /System/Library/LaunchAgents contains system agents run on behalf of the logged in user

- /Library/LaunchDaemons contains global daemons run by root

- /System/Library/LaunchDaemons contains system daemons run by root

You can create new daemons and configure existing ones with the command line program launchctl.

Conclusion

There are other non-user folders hidden away on your Mac, but those above are the most commonly accessed. You can learn more about how Unix file systems are organized by checking out the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard, which explains the requirements and guidelines for Unix-like file and directory placement.

You might also like the following posts:

Create a Bootable Clone of Your Mac for Easy Backup

Install Kexts on a Hackintosh or Vanilla macOS

Pro Terminal: Automate the Boring Stuff with launchd